An Ode to Independent Fashion Designers

It is undeniable that the designers are the ones who create the proposals that are presented at fashion shows. In today's society, which does not exclude the Portuguese reality, the designers that are part of the Lisbon Fashion Week calendar are categorized as Independent Fashion Designers. To whom Aako and Niinimäki (in Fashion Practice, 2018, p.358) refer as follows:

"Independent fashion designers represent a new type of entrepreneur for whom running a business is not primarily a way to make money and advance socially, but rather a means to achieve a lifestyle that allows them to realize the dream of creating their own brand.”

Independent designers are characterized by several authors as creatives who compromise their financial stability in favor of creating their vision for Fashion, and as we have seen, ModaLisboa enables this creativity without business concerns, while young designers discover themselves as people and professionals.

Even though Fashion is considered a creative industry, it is above all a business, a billion-euro business on a global scale.

The alleged lack of business knowledge of many independent designers is thus widely discussed, a fundamental problem - since this component is missing from study plans, and not only in Portugal, but even at the reference for Fashion education - Central Saint Martins, where although there are summer courses dedicated to Fashion Business, this topic continues to be omitted from the study plan for the degree in Fashion Design.

Regarding the Portuguese reality, since 2012, with the start of the Fast Talks project, which was followed by many other initiatives, ModaLisboa has begun its journey in Education for Fashion, other events will mimic this response.

And, although such events integrated into Lisbon Fashion Week have always been open to the public, the participation of students/aspiring designers has always been more noticeable in relation to the fashion shows.

Although the objective of this chapter is to theoretically frame this topic, there are still questions to be answered, and if they do not exist, it would probably not be pertinent to propose an investigation:

How can we raise awareness among future fashion designers so that they have a more panoramic view of fashion?

In what way can the Academy, within the scope of teaching Fashion Design, in addition to teaching in terms of project execution, give aspiring Fashion designers a more comprehensive perception of Fashion and, mainly, focused on the business and entrepreneurial aspect of Fashion?

This issue is highlighted by Thibaud Guyonnet (in an interview with Natassa Stamouli, 2023), the founder and creative director of the concept store Voostore. More specifically, he points out that one of the main mistakes young designers make when presenting themselves to retailers and the market in general is to present their pieces without mentioning prices. Often, they do not know how to calculate the prices of their pieces and assign a monetary value to their work.

How can financial support and logistics be raised to help established designers grow their business capabilities?

Let's establish a comparison between Nuno Baltazar and Marta Gonçalves, it is possible to infer, with the help of the authors Aakko and Niinimäk (in Fashion Practice, 2018, that the two creators can be considered what the authors call “fashion designer-entrepreneurs”, a characterization to which they refer in the following way:

“Fashion designer-entrepreneurs are not all the same, there are many ways to do it and manage the business.”

Therefore, the two examples given are representative of two different positions of ‘designer-entrepreneurs’, positions that, as we have seen, are not exclusive to one designer or another. The authors refer to the dream as one of the great drivers. And although this utopian element can be unifying, in many cases, facing reality is a differentiating factor.

When, over the last decade, we have heard testimonies from fashion designers who are currently over, in general terms, 35 years old, we could say that they began their careers in the 90s, but such a statement would exclude, for example, Luís Carvalho.

Many people talk about the lack of private investment in their brands. But investment from outside the designer, in his eponymous brand, causes hypothetical problems.

The author of The Fundamentals of Fashion Management (2018), Susan Dilon joins the aforementioned authors of the study ‘Fashion Designers as Entrepreneurs: Challenges and Advantages of Micro-size Companies (2018) in raising such issues closely linked to freedom.

Creative freedom, but also in deciding the lifestyle of the ‘designer-entrepreneur’ and those around him/her. According to the authors, these metrics of well-being, creative freedom, community and sustainability are more defining of success, for many independent designers, than financial well-being.

When we talk about sustainability, we are not just talking about environmental sustainability, and this is reiterated by the various sources consulted for writing this dissertation, we are talking about financial sustainability and human well-being.

Therefore, from the moment there is an investor in a company, regardless of the percentage of compensation given to the investor, the possibility of ensuring the well-being and appreciation of an independent designer's team is no longer in the hands of the creative person himself. Likewise, financial sustainability may be compromised by the return on investment.

This need for feedback could compromise other areas of the brand, more related to the design process.

Such considerations and conceptual relationships are established based on learning acquired in the researcher's previous training, whose supporting pedagogical material may be considered within the scope of the bibliography.

It is also important to remember another danger of the presence of investors in independent designer brands, the loss of legal and business rights to the use of one's own name, as happened with Ana Salazar.

On continuing the review of Dilon's work (2018, p.141), the following quote and its explanation will serve as a starting point for a more in-depth contemplation of the impact that the action of the ModaLisboa Association has on a preponderant part of the Portuguese fashion system — independent designers or ‘designer-entrepreneurs’ and their respective brands:

“When organizing fashion shows, designers realize how expensive they are and how time-consuming and work-intensive they are. It is not a task for just one person, which is why many designers hire a team to achieve better results through collaborative work.”

Therefore, if we are referring to the main platform and the ModaLisboa LAB platform, the following costs inherent to a fashion show are covered by the aforementioned non-profit organization: installation of temporary architecture, set design, benches/chairs for guests, lighting and sound equipment and respective professionals; production assistants to coordinate the volunteers who welcome guests, help organize the fashion show venue or work as backstage props; hiring of models, casting management; make-up artists; security and cleaning... and the list could go on. These costs are covered by sponsorships, partnerships and exchanges.

But what is important to highlight is not only the budgetary savings that Lisbon Fashion Week provides to the micro-businesses of fashion ‘designer-entrepreneurs’. As has been mentioned in several press articles, over a wide period of time, by several fashion designers — without the existence of ModaLisboa, which later, with the developments in several initiatives to promote Portuguese fashion, would take on the name ‘fashion week’, they would not be able to hold fashion shows to promote their own brands.

To understand the present in its scope and with greater clarity, it is necessary to understand and know the history and stories that brought us here. Hence the need and methodological choice of consulting archives relating to the phenomenon under study.

It is therefore important to understand that, more than just a promoter of fashion and a home for many designers, ModaLisboa was instrumental in the acceptance of fashion as a professional activity and a creative industry of great importance to Portuguese society.

To better explain the issue we intend to address, we will do a bit of auto-ethnography: the whys and reasons for choosing the topic to discuss have very personal roots for the master's student, not only in this role as a researcher.

When, over time, people outside the Fashion area and quite distant from its surroundings argue, with a lack of reflection, their strong conviction that Fashion has no future in Portugal or its small presence in relation to other international panoramas, they open the door for the reflection that they did not do, due to lack of curiosity or knowledge, or even ignorance, to be carried out in the appropriate place, that is, in the present investigation.

In a country that lived a predominantly rural life, which since 1933, lived under the rule of the Estado Novo, and under the influence of its later dictator — António de Oliveira Salazar, since 1928 — values such as modesty, an intensely hard-working spirit, a marked religious fervor, and contentment with poverty were strongly celebrated by the paternalistic, castrating and sexist State.

All of these factors were antagonistic to the practice of fashion as a discipline in Portugal, since the ideas were imported. With the Revolution of 25 April 1974, the trajectory of Portuguese fashion also underwent a revolution, beginning a completely new course. The Haute Couture houses, as they were called and called themselves at the time, of experienced fashion designers who imported their patterns and ideas, mostly from Paris, ended up closing down as a result of this historic event.

Once the production processes based on the import of Parisian Haute Couture toiles were discontinued, the national ateliers that did not close would adopt the ready-to-wear system. Thus, although fashion in Portugal does not have as much historical tradition as the acclaimed fashion four, the so-called fashion capitals — Paris, London, Milan and New York — it is a fallacy to say that one of the most expressive Portuguese creative industries has no future.

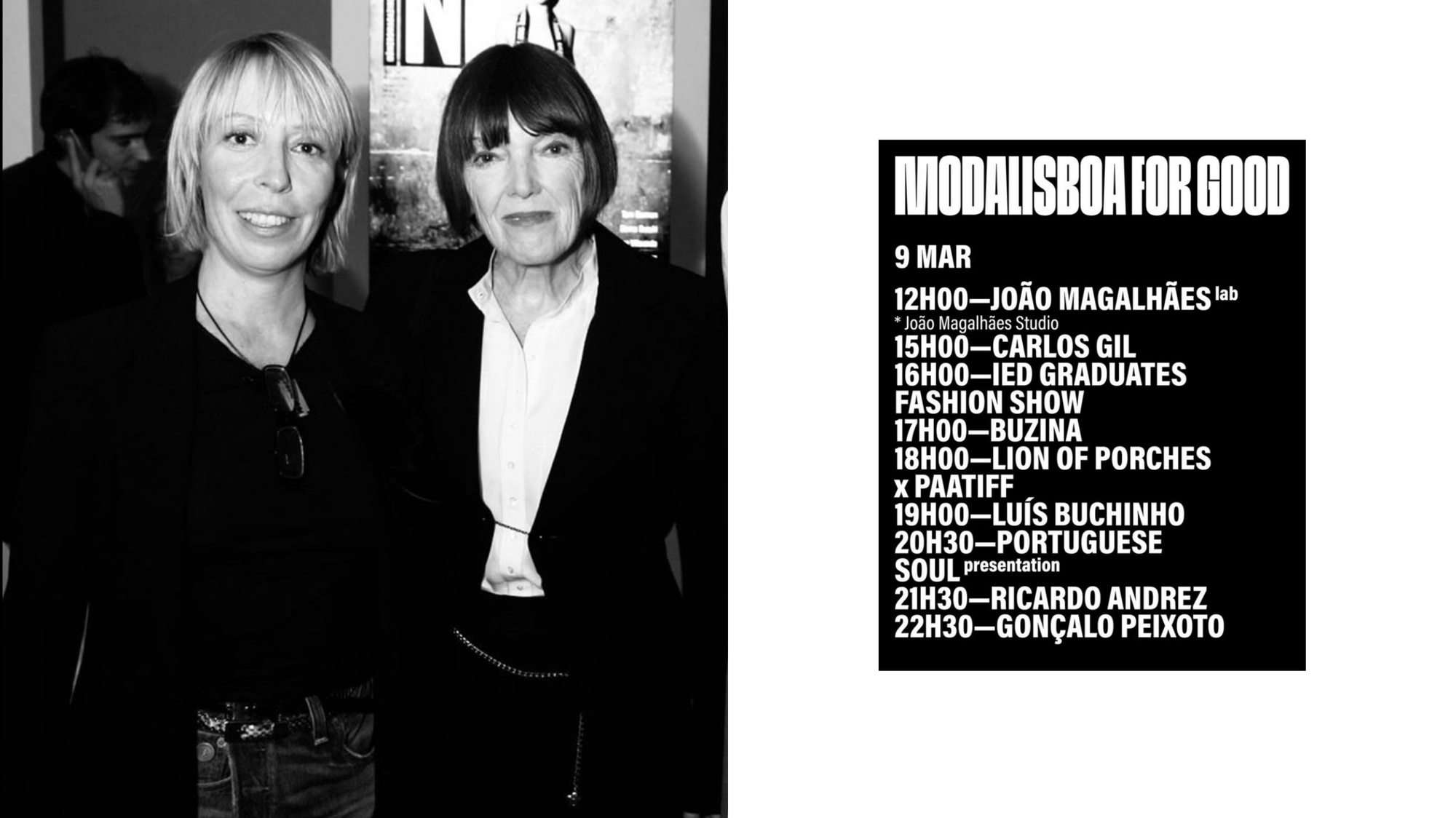

We must remember the words of Mary Quant, when she attended the 23rd ModaLisboa in 2004, when she was asked to “say a sentence for the future of Portuguese Fashion”, to which the unavoidable fashion icon, emblematic designer of the spirit of Swinging London, replied: “We need you and your ideas! Keep going!”

As we know, the impact and true value of ideas lies in their materialization and presentation, and a presentation infrastructure is being discussed here - Lisbon Fashion Week.

Given the fact that, as already mentioned, Lisbon Fashion Week is the largest project of the ModaLisboa Association, a project in itself. Let us use Stark's (2018) studies to better understand the value of the fashion show. The professor at Regent's University sees the fashion show as a powerful tool for promoting brands/designers, with a view to arousing pleasure, interest and enthusiasm that will (possibly) translate into purchases.

The translation into sales depends on the designer himself in terms of the PR work done after the show. Stark (2018) states that doing PR during the show itself is a very difficult task and difficult to coordinate. In the case of ModaLisboa, the organization provides specialized professionals to designers before and during the shows.

Jon Cope and Denis Maloney (2020, p.99) are adamant about the influence that a Fashion Week has on a designer's reputation:

“Being included in the official calendar of a fashion week sends the following message: that the brand is a brand to invest in and believe in.”

The continuation of this quote clarifies the importance of ModaLisboa in supporting independent designers, as well as what distinguishes it from its counterparts.

It does not ask the designers who are part of its calendar to pay an exorbitant amount of money as a requirement for membership, thus giving prominence and equal opportunities to new brands. We also realize that, although increasingly expensive, the Portuguese capital continues to be more accessible to creative activities than many other European capitals.

As the book “Fashion as Creative Economy – Micro-Enterprises in London, Berlin and Milan” (Angela McRobbie & Daniel Strutt & Carolina Bandinelli, 2022) proves, these authors address a very pertinent topic, which is almost never discussed in the fashion industry and question institutions that have been almost sacred until now.

London is not a paradise for independent fashion designers.

It cannot be when the debt involved in studying at Central Saint Martins or the London College of Fashion would never be less than 50 thousand euros. This is where the big question arises: how to start a designer fashion brand with such a high student debt. Even if it could be independent of large economic groups, it would not be independent of time. The time it takes for a Small Medium Enterprise (SME) to make a profit, capable of covering the initial investment plus the designers' student debt.

Given the global economy and the need to add housing and subsistence expenses to the cost of tuition fees, there will not be many students whose families will be able to pay for this without resorting to credit.

Therefore, few will have the possibility, beyond what is described, of financing their children in establishing an independent brand. And the use of a word that derives from the verb to establish was not in vain, it goes beyond creating, it entails the waiting time that will lead to eventual success, even though this is a rather subjective term.

Although London is not a total paradise for independent designers as the aforementioned authors claim, there is something that makes London extremely appealing to young fashion designers - the possibility of reconciling the stability of a job in their field with the incubation of an authorial brand.

In other words, a designer can be employed by a renowned brand, as was the case of some young Portuguese people at Alexander McQueen, where they can gain new skills and develop their network, in addition to the stability that a salary offers.

Being able to test your own brands part-time. Conjecture that could continue for years, or that could trigger two different situations.

The brand that was being developed as a personal project in incubation grows and becomes successful, and the designer decides to say goodbye and dedicate himself exclusively to the brand he created. Or the brand is revealed to be a mere laboratory experiment and ends, with the security, albeit relative, of a job.

In Portugal, there are not many infrastructures that allow for broad employability in the fashion sector, so there is a great need for the creation of micro-enterprises and employment itself. Something that in our country is not exclusive to the fashion industry.

Nowadays, at the heart of the Fashion Industry are Luxury brands, which go far beyond Fashion — they encompass an entire lifestyle.

What used to be the spectrum of Fashion is increasingly reduced, with fast fashion at one extreme being completely unsustainable production, completely unfair prices and exploitation of labor, as a new type of human slavery.

Referring to specific cases that are part of the history of ModaLisboa, it is possible to analyze three different examples in this context: Constança Entrudo, Joana Duarte and António Castro. Constança Entrudo worked at the luxury brand Balmain in Paris, testing her eponymous brand in her free time. As the brand grew, she left Paris and settled in Lisbon.

Joana Duarte graduated in Lisbon, and after completing her studies, she decided to start her own job and embark on a mission to perpetuate Portuguese traditions combined with fashion design, creating Béhen.

António Castro tested his own eponymous brand, presenting his work on ModaLisboa's Workstation platform, although he chose to dedicate himself to his duties in John Galliano's team at Martin Margiela.

On the other hand, we have luxury brands, which may seem to be the complete opposite of Fast Fashion, but perhaps they are not.

Because while on the one hand they don't produce many clothing items and accessories, on the other they produce perfume, cosmetic and make-up licenses almost unbridledly, as these products function as souvenirs of the grand fashion shows of renowned brands, allowing, through such products, to acquire a little bit of the dream.

When mentioning the Fast Talks of the Core edition, we established a comparison between the younger designers, but with a solid career, and the designers who could be described as “renowned”, directly and indirectly concerning the à La Carte edition. In addition to the already mentioned fast talks, we will make a slightly different parallel, between one of the designers who was part of the calendar of the first edition of ModaLisboa; and designers who began their careers and joined the calendar in the last decade.

A cross-reference is made to a report, which could be considered, to a certain extent, ethnographic, published on the website of the newspaper Público, entitled “What are the final preparations for ModaLisboa like?

An afternoon with the team “putting out fires”, where we are introduced to some members of the non-resident team and their roles. As well as the change in routines and tasks of the professionals already mentioned who are part of the team throughout the year.

Tiago de Sousa, sponsorship coordinator, ensures the comfort of sponsors' representatives during the event, who occupy their assigned seats in the fashion show room. Célia Félix is responsible for the commercial management and sponsorship portfolio, ensuring the budget that makes the event possible.

Private sponsorship for this edition was 449,624 euros, with the contribution of 350,000 euros from the City Council, the budget amounts to 799,624 euros, which for an event of such magnitude must be meticulously managed. The ModaLisboa Association therefore has a financial director — Pedro Carvalho, who also has the help of Sofia Barreto.

But let's go back to the "firefighting" that reporter Inês Duarte Freitas witnessed, where the entire team from the Press and Communications Office was involved: Communications Director Manuela Oliveira, who is the link between the press and the designers; António Custódio, who, on the eve of the event, is stepping up his responsibilities in managing social networks and creating content for them; and Irina Chitas, who is in charge of the logistics of press releases; and Fátima Barros, who has been the director's secretary for over 26 years.

Part of the Master's dissertation in Fashion Design "The role of the ModaLisboa Association in the Portuguese Fashion System" by Vera Lúcia Mendes, March 2024.